Police carding not racial profiling, probably

The review is in

It wasn’t quite a last-minute release before the long weekend, but the review of Edmonton Police’s carding practices came pretty close. The review was made public last Wednesday, almost a week after the Edmonton Police Commission got its chance to read it.

If you want to know what this is all about, we did a fairly deep dive on the issue a few months ago. And we tracked all the news last year after Black Lives Matter-Edmonton (and the CBC) released data that showed racial profiling, with Indigenous peoples and Black Edmontonians stopped disproportionately. Carding, also known as a street check, is when police stop someone on the street and collect their personal information, unrelated to an active investigation.

Alright, now onto the report. It doesn’t conclude that police are stopping people based on racial bias, but it also doesn’t definitively say that’s not happening.

Two big reasons for that muddled conclusion are the lack of fieldwork for researchers, which could help to show why officers are conducting the street checks and the dynamics of encounters, and the fact that only 16.5% of what police filed as a street check are actual street checks.

The vast majority of the 27,000 encounters reported as street checks in 2017 were related to other crimes and investigations, which the researchers did not count as street checks. So, obviously, one of the recommendations is around clearing up this policy and logging information properly.

More fieldwork, or being able to monitor interactions from body camera video would allow those reviewing the process to parse what’s happening on the street and the interactions.

“Community members often using the words ‘lack of respect’ and ‘dehumanizing’ to describe the dynamic. There were also concerns that the officers’ treatment of persons during street checks might exacerbate trauma and other challenges that persons in communities of diversity are experiencing.”

The review notes how important it is to consider the perception of people being stopped by police, and the feeling they are being targeted or criminalized. They may also feel there’s no good reason for police to be stopping them.

“The results of the analysis revealed that EPS officers generally have the lawful authority to conduct a street check. In a number of instances, however, this authority was provided by by-laws that cover behaviour that is subject to highly-selective enforcement, e.g. defective bike equipment, interfering with park furniture, yet it provides the officer with the authority to engage a person.”

Here we see why more reviews of carding, and what results it leads to, is important for the police to be able to judge its effectiveness as a policing tool, and for vulnerable and diversity communities to be able to judge it the same.

Speaking of effectiveness, I noticed in one story that carding was being connected to solving 14 crimes.

14. Out of 4,400 street checks.

That’s a 0.3% rate, at best.

This is why more reviews are needed. I can’t see the EPS wanting to spend hours and hours of time, through thousands of interactions with the public, to solve so few crimes. The review even notes that Edmonton Police seem to spend less time on proactive policing than other forces, so there’s a possibility this helps point them at more community-based interactions.

I bet we could prevent more than 14 crimes through community and social supports and programming. If we consider a street check takes 15 minutes, that’s more than 1,000 hours worth of programs (or police working with community groups and individuals in non-policing ways).

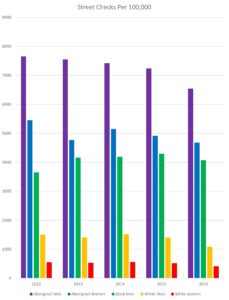

EPS data showing who gets carded in Edmonton. image: Progress Alberta/BLM

This all began because of the reports that Indigenous peoples and Black Edmontonians were being stopped way more often than they should be, considering how much of the city’s population they made up. The report mentions that looking at Edmonton’s overall population isn’t fair when we try to see if certain groups of people are over-represented. It asks to look at available population, that is, people living in the areas where more carding happens.

But let’s contrast that with, say, the new report calling for change in Alberta’s child care system. This is a system that will spend millions more to try and reduce the over-representation of Indigenous children in care. We’re not talking about available populations here. And it’s pretty universal that this is how we need to change systems like children in care and justice and imprisonment, particularly for the over-representation of Indigenous peoples.

Seems like we could indeed apply similar examinations to who Edmonton Police are stopping and logging information on. I don’t think this review is the last word on potential racial bias in policing.

“The information contained in SCRs is viewed by EPS sworn and civilian members as a critical component of police work, including investigating crimes, locating missing persons, solving crimes, and crime analysis… There are currently no other mechanisms in the EPS to gather this type of information and make it readily accessible to patrol officers, investigators, and analysts.”

So, police are going to log people’s personal information in official law enforcement systems because they don’t have a filing cabinet or Evernote account? I feel like there are some easy changes available here that protect people’s privacy.

Some of the recommendations: more training around interactions with the public, particularly around communities of diversity and their history and culture; increasing diversity in police ranks; better communication between frontline officers and senior officers and with the community at large; effective resourcing to allow police officers more time on proactive duties, instead of just responding to calls and working cases.

Another recommendation is to publish street check data throughout the year. Let’s hope that happens so this can be more properly reviewed as a policing tool, for the EPS as well. This one comes from the provincial privacy commissioner.

There was also a recommendation to further study the interactions between private security companies and communities of diversity. This one is sort of out of the hands of EPS or the Edmonton Police Commission, but the Alberta Government could make it happen. We know that private security ranks have exploded in the last few years, with oversight scrambling to catch up, and this could be part of the larger discussion around policing neighbourhoods and communities.

Edmonton police will continue to perform street checks, while adopting recommendations of this report. How, and if, things change will ultimately be up to the Edmonton Police Commission. It has to determine if the practice achieves results it seeks from the EPS. There’s always a chance the Alberta government brings in new rules to govern all police forces, as happened in Ontario, but there’s been no indication this is an issue of importance provincially.

It’s worth noting, too, that this review is really thanks to members of minority and vulnerable communities asking for oversight. Demanding it. They will have to remain involved, of course, because the lack of clear targets from the review make it too easy for EPS to claim change while the perception, or reality, of targeting remains.

You can see the full report, and the executive summary, at the Edmonton Police Commission’s website.

If you enjoyed this story, and want to see more like it, consider supporting us.

Support EQ