Happening Today

Sorry, event listing is not available.

Keeping up bike lane momentum in Edmonton

Bike lanes make sense on the southside

Written by Jeff SamsonowTLDR;

Bike lanes are cost effective, overdue in many neighbourhoods and create a sense of community. It’s time to keep up the momentum and build more.

This is the year Edmonton can build on its commitment to active transportation and bicycling.

We’ve got construction wrapping up on the 83 Avenue bike lane this summer and testing continues on the new downtown bike network. But there are two milestone decisions coming which will really signal how dedicated we really are to being a city with bike infrastructure.

The Edmonton Bike Plan (which used to be called the Bicycle Transportation Plan) is getting its first update in a decade. Obviously a lot has changed in Edmonton since 2009, as we have moved away from cyclists sharing lanes with drivers (which didn’t end up going so well) to now building actual separated cycle tracks that give cyclists their own space on the road. We’re even beginning to see talk of a bikeshare in Edmonton, allowing people who don’t own their own bike to cycle.

This will be a major update to a key transportation plan at a key time, so watch for public engagement opportunities over the next year to make sure you’re helping shape our cycling and commuting future.

The other big decision comes in April, when city council is likely to consider a southside bike network, similar to the one we have downtown. This would be installed throughout the Old Strathcona area, connecting the neighbourhoods of Strathcona, Garneau and the University of Alberta.

There are a lot of good reasons to build this southside network right now.

This vs. That

Whether you call it a bike network or bike grid, we’re talking about the same thing.

It is a grid of bike lanes and connections within a neighbourhood, which could include multi-use paths (MUPs), that itself connects to Edmonton’s larger bike network. I think, however, since we have gotten used to calling it the “Downtown Bike Network” and this southside installation could operate in a similar, adaptable, fashion, it makes sense to call it a network too. Network and grid are pretty interchangeable as Edmonton just begins to build out its bike infrastructure though.

Speaking of being “adaptable” here’s what that means: the barriers separating cyclists from drivers aren’t permanent. This is what we’ve got downtown.

There are small, movable curbs, pylons and bollards and even planter boxes. If one of the streets needed to be closed for massive construction, for example, the pieces could be moved to the next street over if that was preferable to waiting things out. Or, if everyone refused to bike down 103 Street and used 102 Street, the City could also pick up and move things over if that made more sense for transportation efficiency.

This is compared to permanent bike infrastructure like we have on 83 Avenue. The barriers separating cyclists from drivers there are poured concrete, they built right into the street, and we aren’t changing the route anytime in the near future without spending a lot more money.

In this story:

- Communities that deserve bike lanes

- City strategy is about bikes

- The business case for bike lanes

- Bike lanes stretch tax dollars

- Time to make the move

Building Community

“Our streets are what bring people of all ages, abilities, and backgrounds together. When residents choose to walk or bike to get places, we see one another’s faces. We can say ‘hello,’ smile, stop to catch up or plan an impromptu BBQ.”

Julie Kusiek is passionate about making sure her neighbours have chances to meet one another, talk to each other and move around Queen Alexandra without a car. She lead a group of tireless volunteers for years in the QA Crossroads and Engage 106-76 projects, as Queen Alex tried to incorporate more active transportation – sidewalks and bike lanes – into the community’s neighbourhood renewal project. The work focused on 106 Street and 76 Avenue, both of which now have new bike lanes criss-crossing the community.

“Making 106 Street and 76 Avenue into our neighbourhood’s showcase streets means that it is more pleasant to walk and bike, and that vehicles are moving just a bit slower too,” Kusiek says.

“This makes the lives of residents who live along these streets better. They can more comfortably spend time in their front yards, creating yet another opportunity for neighbours passing by on foot or bike to say hello and hear each other because vehicle noise is reduced by slower speeds.”

A new bike grid could connect southside communities already biking a lot more than others. Just 60% of people in neighbourhoods like Strathcona and Queen Alex use a personal vehicle as their primary mode of transportation and Census data shows rates of active transportation are up to five times as high as Edmonton averages.

“What the QA Crossroads and Engage 106-76 project did was take an existing demand for walking and biking and find a way to build appropriate infrastructure to facilitate that kind of movement,” Kusiek says.

The southside bike grid could build on this work, giving neighbourhoods already biking a better, safer way to get around. Across Whyte Avenue from Queen Alex, Strathcona is about to undergo its own neighbourhood renewal, meaning streets and sidewalks will be completely replaced. Volunteers in that neighbourhood have also teamed up with the City like Queen Alex did and also have a vision to include more active transportation once concrete is poured.

So, the timing for the southside grid is perfect (and overdue). With Strathcona renewal running 2019-2021, there’s even time to set up some pylons and counters this summer to figure out the best possible streets for bike lanes and connections to be implemented as part of the construction.

Although Conrad Nobert, the co-chair of the Strathcona Working Committee leading consultation on that neighbourhood’s renewal isn’t quite sure we have to do much in the way of testing. (The committee is a partnership of volunteers and City staff.)

“Installing good bike infrastructure is not rocket science,” he says.

“We tend to act as if we’re inventing nuclear fusion or something when we put this stuff in, and that it requires pilot projects and tests to see if it will work. High quality bike routes are installed everywhere in the world, and they are successful if designed well. Edmonton now has some experience with their design, so I think they could be installed permanently, after a thorough consultation has been conducted, as renewal is being done. That said, a portion of funds should be held back for monitoring and a few tweaks once operations are observed for 18 months or so.”

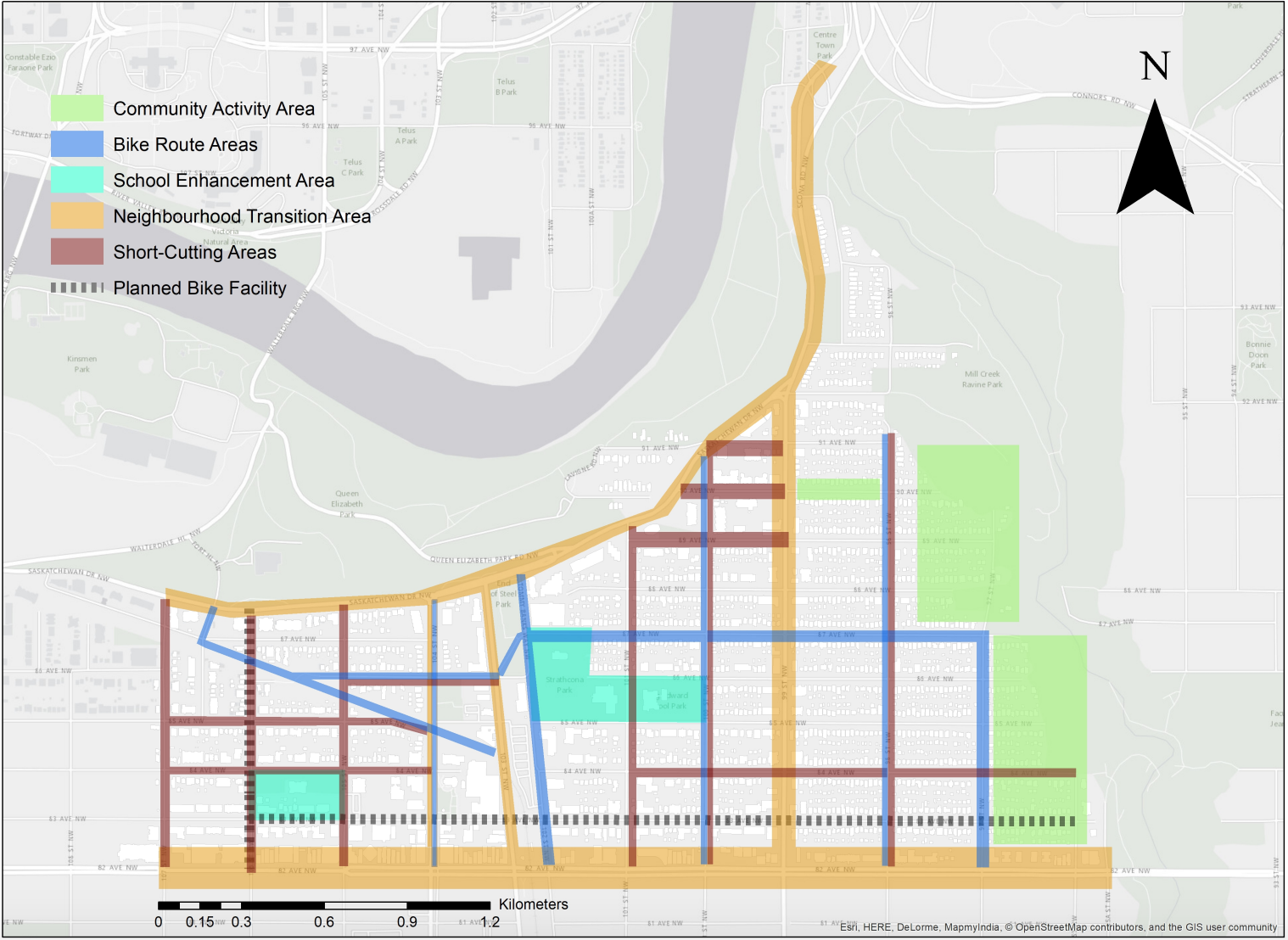

Here's one potential idea for more bike lanes and routes on the southside (in blue), as proposed in a visioning document from the Strathcona Community League.

Here's one potential idea for more bike lanes and routes on the southside (in blue), as proposed in a visioning document from the Strathcona Community League.

Building for the future

Another reason Edmonton should move ahead with the southside bike network is that we have a big pile of planning and visioning documents we’re supposed to follow.

“We found a way to give the City the courage it needed to implement something a lot of Edmontonians have already said they wanted,” Julie Kusiek says of the work of Queen Alex volunteers.

The City of Edmonton is guided by master plan documents known as “The Ways”. The Way We Move is our transportation plan. The Way We Grow is our growth and development plan. Those two play a role in making decisions about bike lanes.

“One of the goals in The Way We Grow is ‘Complete, Healthy and Livable Communities’,” says Kristi Bland, communications advisor with the City’s Integrated Infrastructure Services.

“This focuses on designing communities to encourage healthy lifestyles and social interaction for people. The growth in the bike lanes supports this and also supports the transportation mode shift goal in The Way We Move. We are working to improve the commutes of all Edmontonians.”

Nobert sees active transportation building these goals right into our neighbourhoods.

“It increases our quality of life and provides a safe healthy transportation option. Strathcona can, and should, become a community that makes people healthier when they move into it, by how it affects their daily choices through urban design.”

If we’re talking about building our neighbourhoods for the future, you know we’re talking about increased density, particularly in the mature neighbourhoods in our city core.

“A lot of older homes are reaching the end of their life,” says Kusiek of Queen Alexandra.

“Developers are buying one home and replacing that one home with sometimes up to four units on that lot. For example, a front-back duplex with basement suites. More and more families are wanting to move into our neighbourhood to be close to work, schools, and other amenities.”

Of course, if you’ve paid attention to the infill conversation in Edmonton, you know that too many of these homes remain out of the price range of a lot of people and families, particularly in comparison to some houses way out in the suburbs. We just haven’t refined the process yet to make infill quick and cost-effective to build.

“So, one realistic strategy to afford a new infill in our neighbourhood is to drop a car,” Kusiek points out.

“Without an extra car payment, insurance and maintenance costs, all of a sudden you save a bunch of money every month. Bonus points if you bought a place with a legal basement suite you can earn revenue from while living in the main floor. You might even find a tenant easier because they can save money by walking and biking places.”

Increasing density in our mature neighbourhoods is seen as a must for Edmonton to reduce sprawl and keep taxes relatively low (the suburbs cost us more) but we’re also dealing with neighbourhoods that have limited to zero space to add more traffic lanes.

“We’re already a community of 9,000 people. If our population doubles over the next 15-20 years, and every one of those people exclusively drives a car for transportation, our quality of life will be low and transportation will be very slow and unhealthy,” says Nobert of the Strathcona neighbourhood.

“Given that walking and biking take so little urban space, active transportation is the perfect complement to increased density. It will allow Strathcona to reap the benefits of density while mitigating the downsides (traffic and parking pressures).”

Complete Streets and the Main Streets Guideline are documents that guide decisions on how to build our roads for all users, including people walking and biking. They are becoming a bigger part of neighbourhood renewal discussions because our most walkable and urban communities still have many overbuilt roads and renewal is a time when neighbours can ask for changes. The Jasper Avenue pilot is an example of testing these kinds of changes before construction, and the southside renewals coming are also good times to implement safer streets.

Then there’s Vision Zero. That’s the plan to eliminate all deaths and serious injuries on city streets. It’s a bold strategy the City is still struggling to figure out a path toward, but it’s also key when we’re talking about adding more bike lanes.

“By designing roads based on all forms of transportation, then we are designing with safety in mind,” says Gary Dyck, the communications advisor for traffic safety with the City of Edmonton.

“More cyclists on the road can help reduce crash risk for each bicyclist. In Copenhagen, it was found that between 1990 and 2000, a 40% increase in bicycle-kilometers traveled corresponded to a 50% decrease in seriously injured bicyclists. A 2003 study of California cities found results substantiating this idea of safety in numbers. Based on 68 California cities, but unfortunately for only one year of crash data, the results showed that the individual chance of a bicyclist or pedestrian being struck by a car drops with more people biking and walking. The hypothesis is that drivers change their expectations, based upon their perceived probability of encountering a bicyclist.”

And it’s not just people cycling who could be safer on Edmonton streets. Recent stats out of Toronto about that city’s Bloor Street project show drivers are hitting other drivers less since bike infrastructure has been installed. That’s right, bike lanes are keeping everyone safer thanks to how the road design changed. Why wouldn’t we want more of that in Edmonton?

In our downtown there were three cyclist injuries the last half of 2017, according to the City. We’ll see more official stats in June, one year after the first lanes opened. But if other cities can show us the likely trend, it’s toward fewer collisions.

Building business

Since we’ve now mentioned the Bloor Street project in Toronto, let’s look at what it can also tell us about how bike lanes could help businesses. Calgary’s lauded bike network also provides a look at what’s likely to happen in Edmonton. Yes, I’m going to make the pitch that bike lanes will build Edmonton’s economy.

Toronto set up bike lanes on Bloor Street as a pilot, and they’ve kept them because they’ve hit just about all measurable targets, including keeping money flowing to businesses.

“Cyclists also tend to observe their environment at a more human scale which, as we have seen in Toronto’s Bloor Street pilot, leads to more people going into stores and [patronage of] businesses over time,” says Ian O’Donnell, the executive director of Edmonton’s Downtown Business Association.

O’Donnell is among those waiting for more data from the City on our first year of bike lanes because they’ve been a divisive topic downtown, with some people very passionate about them and some very frustrated. The conversation could get clearer in Edmonton when we see how things are actually going.

We do see more businesses embracing the bike lanes, as has happened in other cities (like Vancouver).

“[They’re] using them in marketing promotions/programs, adding secure bike lock stations, opening the fronts of their business more to bike lanes,” says O’Donnell.

Calgary’s bike lane study shows very little change in walk-up traffic and average spending by customers. Even though spending was down, the numbers are compared to 2014 and may also reflect a drop in spending because of our oil-related recession. (It also saw similar positive results on safety and traffic flow as Toronto.)

For downtown and Whyte Avenue commercial areas, a connected bike network could be beneficial with more regular stops from cyclists at shops and businesses.

“An expanded network will be very positive in that it will provide even more people the option and reason to use it as there will be more destinations and a more complete system,” O’Donnell says.

We met with @Cartmell_Ward9 to discuss the #yegbikegrid earlier in September. He was open and willing to listen to our ideas. pic.twitter.com/7OINhbsLXZ

— Paths for People (@pathsforppl) October 11, 2017

Thinking a little bit bigger than just our downtown and Old Strathcona, bike lanes could be a way to attract and retain talented and skilled workers, entrepreneurs and businesses. It was a request on Amazon’s recent pitch to cities to bid on a second headquarters for the online shopping company.

“That’s a front-page question,” says councillor Tim Cartmell of bike lanes and mass transit, in a recent interview with Postmedia city hall reporter Elise Stolte.

“The companies know the younger generation wants alternative ways to get around and sees these young professionals as key employees. If Edmonton doesn’t provide that infrastructure, it won’t attract these businesses or keep its youth, he said.”

“It’s an economic development question as much as anything,” Cartmell told Postmedia.

While pitches like the Amazon bid won’t come around frequently, there are plenty of other companies, including some already based in Edmonton, looking for central locations with lots of active transportation connections. The mayor is even trying to get them to move to a so-called “innovation corridor” between our three major post-secondary schools. We can’t add freeways between the U of A, MacEwan and NAIT to move all these additional people every day but we can add bike lanes quickly and cheaply.

(We also see fewer people even getting a driver’s license, creating greater need for reliable multi-modal transportation options.)

An example of how the downtown bike grid works. image: City of Edmonton

An example of how the downtown bike grid works. image: City of Edmonton

Building savings

Alright, if we’re talking about building things cheaply we must be referencing careful use of tax dollars. If the benefits of bike lanes to our neighbourhoods, city planning and businesses haven’t won you over yet I’m sure I can do it by showing how they can do more with your tax dollars.

The first thing to note about the numbers I’m about to throw at you is that transportation costs aren’t an exact science. There’s money for building roads, but that often includes upgrades to traffic signals, signage, sidewalks and other amenities. Same goes for bike lanes, which can include traffic signal upgrades like we saw downtown and a total street revamp like we saw on 83 Avenue. Then, costs like pothole fixes, maintenance, repairs, cleaning and snow removal are shared across all forms of transportation.

But I think we’re talking about numbers that give us a close enough sense of what costs what, to make the case bike lanes are good use of tax dollars.

The second thing to note is that this isn’t a pitch to close all traffic lanes in Edmonton and replace them with bike lanes. There’s no war on cars and these bike lane numbers work best for neighbourhoods where people are already biking, or could be enticed to hop on two wheels. (Though, as councillor Cartmell points out, there’s lots of work to connect these pending grids to our suburbs too.)

Since our current bike lanes act more like arterials for cyclists, I think it’s fair to compare costs to the pending Yellowhead Highway upgrades.

The Yellowhead upgrade is going to cost $1B*. It will convert 25km of roadway to a freeway through north Edmonton for the benefit of around 80,000 daily drivers. That’s about $40M per kilometre or $12K per driver.

All of our current bike lanes – downtown, 102 Avenue, 83 Avenue (when completed to 111 Street) and 106/76 through Queen Alexandra – cost about $20M to build (with some of those costs including road work). They’ve added just over 16km of protected lanes to streets. That’s about $1.25M per kilometre.

*The $1B cost of the Yellowhead upgrade isn’t a final number, and the City will be on the hook for at least $516M, sharing other costs with the provincial and federal government. Around 20% of the vehicles are transport trucks too. So, if we wanted to do a similar breakdown at $516M for 60,000 personal vehicles it’s still more than $8K per driver.

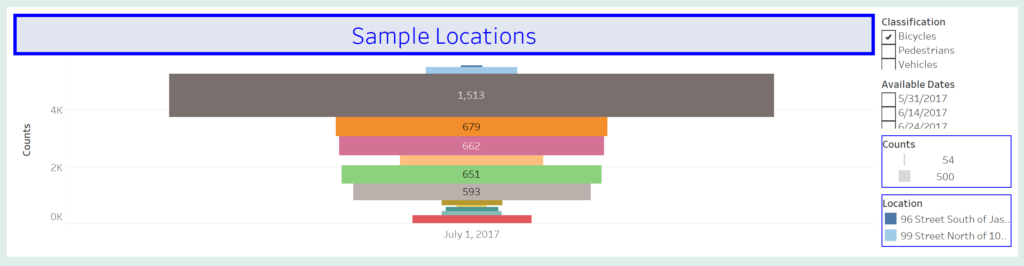

Downtown bike monitoring for July 1, 2017. image source

When we break it down by cyclist it’s kind of difficult because we only have numbers for the downtown (check out the official tracker). This is obviously something the City can be more diligent about, for all modes of transportation.

But let’s take one of the better days downtown in 2017, July 1, and say 5,000 people were cycling on any of these lanes. That’s about $3K per person.

The same day downtown there were 40,000 drivers, so the $6.5M cost of bike lanes and traffic signal upgrades works out to $162 per driver. If adding bike lanes improves traffic flow and reduce collisions like they have in other cities that’s a pretty small amount of money to spend for such improvements for drivers.

Just to be fairer, you can check this document for similar breakdowns of the cost of a trio of road projects. Bike lanes coming in around $1M for every kilometre is as good as other work being done to improve traffic flow, even when not compared to a massive project like the Yellowhead.

One more example. In Queen Alexandra, neighbourhood renewal cost about $35M. That’s a little more than the $31M predicted in early consultation. Over two years, some of the increases could be attributed to inflation, some for extra engineering work or design changes necessitated by things like a tree where one wasn’t expected, road width being off from early surveys, etc. and some of the increases might be for the bike lanes.

Using our earlier math for other projects, the approximately 1.5km of lanes in Queen Alex would cost less than $2M. If that 5% budget increase makes it easier for folks in an increasingly densifying neighbourhood to get around, reduces collisions and creates more business hubs, that’s a pretty solid argument for the extra money. And that’s if even 5% of the budget is solely for adding bike lanes, because we can see from these numbers that a lot of transportation costs get mixed together.

“Walk and bike infrastructure is very cheap already,” adds Nobert.

“It doesn’t need to withstand the beating of 3000 pound vehicles in all seasons. One of the major costs of walk/bike infrastructure is actually the public consultation, which is unavoidable given that any change to public infrastructure will require talking to the community.”

So, using this rough math we can see including bike lanes in road projects in our mature neighbourhoods doesn’t add much to the budget but can produce better outcomes for everyone, including people driving.

Overall budget numbers

When we look at Edmonton’s total transportation budget for building and repairing roads, sidewalks and bike infrastructure the numbers also point to active transportation being a good value for how many people use it on a regular basis.

Over the life of the 2015-2018 capital budget more than $500M went into transportation capital, another $170M for neighbourhood renewal, $27M for street lights and around $40M for active transportation and our new bike lanes. That means people biking are getting infrastructure from maybe 2% of the budget.

If we look at neighbourhoods like Queen Alexandra, Strathcona, Garneau, the U of A and Downtown, we see people walking and biking well over the city average of 5%. This kind of infrastructure goes toward giving many people safe ways to move around Edmonton – ways they are already choosing – and for well less than their share of the budget.

Building bike lanes

I’m not going to end this on a big jumble of numbers. It’s always got to go back to the kind of city we’re building and what our public spaces say about the place we live. For this, Julie Kusiek has a great example of why Queen Alexandra wanted to create more opportunities for interaction between people in the community.

“Recently a neighbour was walking to pick up her child from school. Her younger child had to use the washroom and wasn’t going to make it in time. She stopped in at my place and asked if the younger child could use the washroom and stay to play while she continued on to pick up both our kids from school. This was great as my baby was still napping so I didn’t have to wake her up. All the kids got picked up from school, we avoided wet pants, the baby got to finish her sleep and our bigger kids got to socialize on the way home. Wins all around!”

Safer roads encourage everyone to bike. image source

While this might be a really specific example, it is the kind of thing Queen Alex neighbours thought about when pushing for streets that slowed people down and allowed more travel by foot and pedals.

“This makes the lives of residents who live along these streets better,” Kusiek says.

Neighbourhoods where people are already biking and walking make bike lanes cheap to build, get great value per user (and for taxpayers), build community connections and could even benefit more businesses. Active transportation infrastructure also increases the dignity and safety of everyone on the road, no matter their mode of travel.

“It will mean safer, more active people of all ages. It will mean kids biking and walking to school… being truly family-friendly,” says Nobert.

For all of these reasons (and more), Edmonton should approve a southside bike grid, with adaptable lanes popping up this summer, looking at installing more permanent bike infrastructure during the neighbourhood renewals in Strathcona and Garneau. Then we can connect to more grids in nearby mature neighbourhoods like Ritchie, McKernan, Belgravia and the U of A. Not to mention expanding the downtown and 102 Avenue lanes to Boyle Street and Westmount.

This is a big decision for Edmonton because starting a southside grid this summer can capitalize on the growing use of the downtown network and we could induce demand on bike lanes instead of clogging up streets with more cars and trucks. Delaying could mean people don’t make the switch to a bike because they don’t see the City making their choice and safety a priority.

Contact your city councillor if you want them to think about building out our bike infrastructure, or connect with a group like the Edmonton Bike Commuters (EBC) or Paths for People who will be advocating for these kinds of changes.

Written by Jeff Samsonow. Photos and images via City of Edmonton, Paths for People and Strathcona Community League. Header photo via Paths for People.

Questions about this story? Comments? Get in touch with us.

Disclosures

Jeff Samsonow is a board member of the Strathcona Community League and also volunteered with the Engage 106-76 project.

This story was made possible with the financial support of Paths for People. For more on our content sponsorship, please see our sponsorship policy.

If you enjoyed this story, and want to see more like it, consider supporting us.

Support EQ