Happening Today

Sorry, event listing is not available.

Words on the Street

A revitalized downtown may be creating more space for street harassment.

Written by Jessica BarrettTLDR;

The new entertainment district may not be the only place women face street harassment, but it’s putting the issue front and centre in Edmonton.

A note to readers: This story and related media contain descriptions of sexual harassment which may be triggering.

Natalie remembers the day she finally broke into tears.

It was hot out, June or July, and the 27-year-old was headed back to her apartment in Edmonton’s newly minted Ice District after a dip to cool off at Oliver pool. She’d thrown a simple summer dress over her bikini for the journey. Natalie* says she can’t remember exactly what the man yelled as he sped past her in a car while she waited for the light to change on 104 Street near 104 Avenue, but it was something about that dress, how it revealed her body, how it was, in his opinion, too short. It wasn’t the exact words that got to her anyway. It was the fact that they just wouldn’t stop.

Constant sexual harassment wasn’t what she expected to encounter when she moved into Square 104, across from the Mercer Warehouse, in August 2016. She was excited to be part of downtown’s revitalization. And she was exactly the kind of young, urban professional the city and developers say they’re hoping to attract to the area, engineered around Rogers Place. But after the $600M facility opened in September 2016, both Natalie and her roommate, Brittany Davey, noticed the change. Their neighbourhood became a hostile place.

They first noticed the trash. On mornings after events at the arena, the streets were papered with flyers for a nearby strip club. And then they noticed they were increasingly targeted by groups of often drunk men who flocked to the area.

“Every single time I would leave the apartment I would get catcalled, or someone would yell at me or approach me and just make me so uncomfortable,” Natalie says.

“It got to the point where if I was just getting approached by a random person asking for directions or for money, I would jump.”

The hostility extended into their home. Davey says she was catcalled while on her balcony overlooking 104 Avenue.

The hostility extended into their home. Davey says she was catcalled while on her balcony overlooking 104 Avenue.

“I was definitely yelled at a few times,” she says.

“Something like ‘Show me your tits,’ which is really nice when you’re trying to enjoy your home.”

Whether it was due to the type of crowds heading to events at the arena, or just that more people were coming to the neighbourhood, the women can’t say, but their response was to retreat. They started staying home on game nights, keeping off the balcony and altering the routes they took through the neighbourhood. Natalie even changed how she dressed.

“I would put on what I wanted to wear and look in the mirror and be like, ‘Is this going to encourage someone to approach me?’ If the answer was ‘Yes’ I’d change,” she says.

“I hated that. I hated that so much.”

When Davey moved to Ontario this past fall to go to school, Natalie chose to move out of the area, too.

“I haven’t been back since.”

*We have changed certain names in this story to protect anonymity

Burden of silence

We don’t often associate street harassment with the egregious examples of sexual misconduct that have brought powerful men to their knees in the era of #MeToo, but it’s all part of a sexual violence continuum that pervades our culture, says Mary Jane James, executive director of the Sexual Assault Centre of Edmonton (SACE). The degradation, humiliation and fear women face while on city streets — particularly in hyper-masculine ecosystems fueled by alcohol and sports, where women are regarded as props for the evening — makes many women feel unwelcome and unsafe in their own communities. And yet, too often, we don’t take it seriously.

“People do not think of street harassment — catcalling and all of those things — as sexual violence because it’s been allowed to be normalized,” James says.

“It’s been going on since time began and women were just taught to just suck it up and move on.”

Sexual Violence Resources

If you’ve been sexually harassed or assaulted, or if this story is triggering, here are some places in Edmonton to contact for support.

Sexual Assault Centre of Edmonton – A safe and supportive space where survivors of sexual abuse and sexual assault can exercise their resiliency and strength in healing from trauma. Individual and group counselling and a 24-Hour Sexual Assault Crisis Line (780-423-4121). More information at sace.ab.ca.

Pride Centre of Edmonton – You can also reach out to Edmonton’s Pride Centre for support and resources. More information on their Facebook page.

MacEwan University’s office of sexual violence prevention and education – A resource for students and staff of MacEwan, offering a place to be heard and support services, including confidential reporting. More information at MacEwan.ca.

U of A sexual assault centre – For students and staff of the U of A, a safe place on campus offering support, confidentiality, respect, and advocacy for those affected by sexual assault, sexual harassment, relationship violence, and stalking. More information at ualberta.ca.

Distress Line – If you’re feeling overwhelmed or in crisis you can also call the Distress Line at 780-482-HELP (4357) to talk to someone. More information.

The prompt closure of The Needle Vinyl Tavern in November, after allegations of sexual assault and harassment surfaced, shows that Edmonton — like the rest of North America — seems to have drawn a line in the sand around workplace sexual harassment. Since The Needle closed, demand for a pilot program SACE has offered with the U of A Sexual Assault Centre since February 2017, to make bars and clubs safer for women, has skyrocketed. Once people leave those bars, however, women are often still seen as prey, James says. Compounding the problem, many men who would never see themselves in the same category as Harvey Weinstein, or even Aziz Ansari, think nothing of a drunken catcall on a night out with the boys.

“I really don’t think that a lot of men who engage in street harassment view this as harmful, as a part of sexual violence,” James says. “But it starts there. Rape culture is what’s allowed this issue to be present in our lives for so long, because it’s surrounded in silence.”

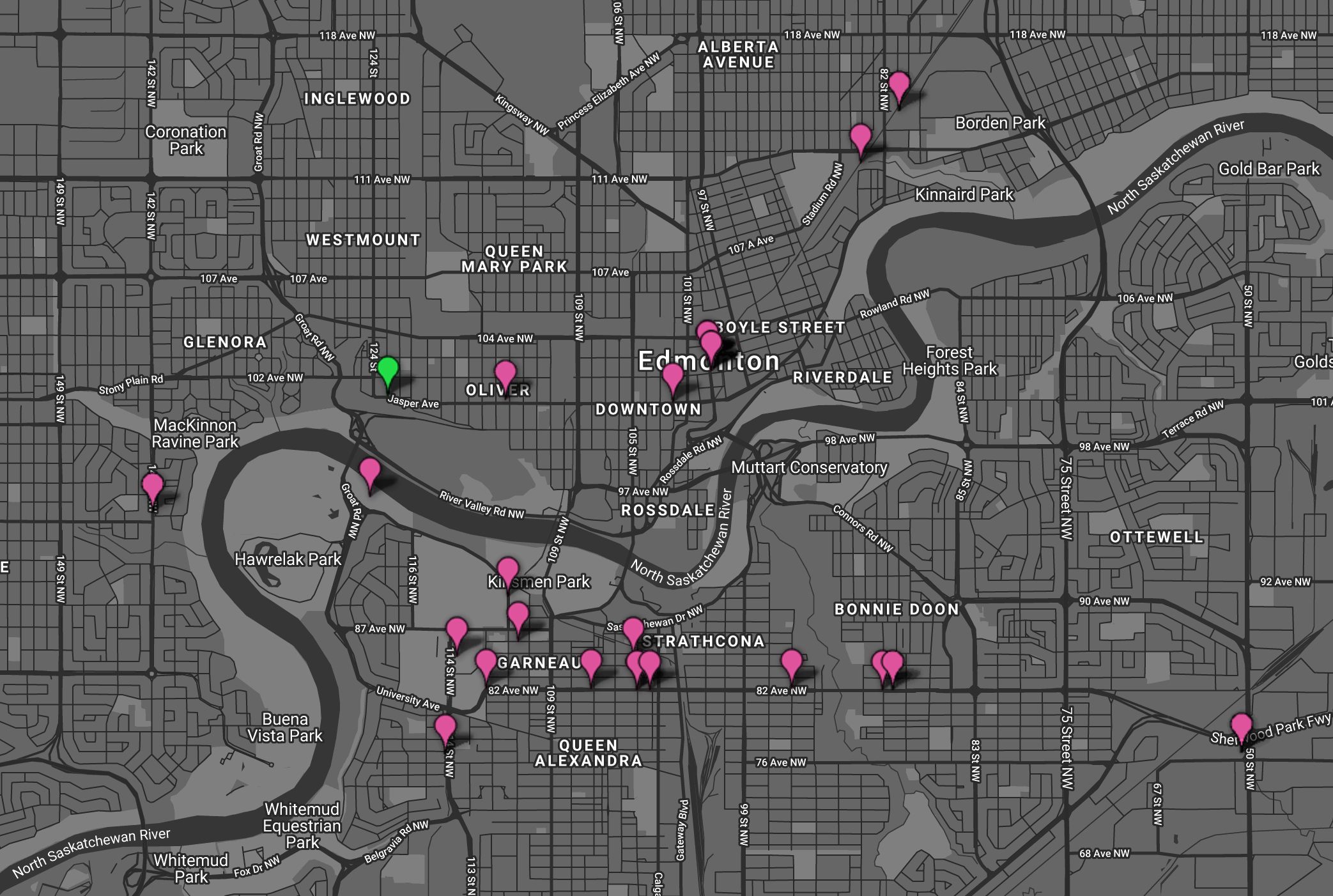

A map from Hollaback Alberta showing some locations of street harassment.

A map from Hollaback Alberta showing some locations of street harassment.

How best to break that silence, however, is a puzzle.

Groups like Hollaback Alberta have surfaced in recent years to support women in reporting street harassment, collecting their stories and tracking harassment hotspots in the city. A 2015 report from the group examined more than 1,000 reported incidents of street harassment in Edmonton, with the vast majority occurring on city streets, in malls and on transit. Jasper Avenue and Whyte Avenue were two of the top areas identified by respondents.

Edmonton Police Service spokesperson Cheryl Sheppard, meanwhile, explained that while isolated catcalls are not technically a crime, women can and should call police when they feel they are being harassed. Collecting data on where harassment occurs can help create long-term strategies to improve police presence, lighting or correct other environmental factors that put women at risk, Sheppard says. But the fact remains that faced with harassment in the moment, most women feel powerless.

Marielle TerHart isn’t used to keeping quiet. The 28-year-old social media consultant, comedian and downtown loft resident says frequent street harassment is her “number one problem with living downtown,” a community she otherwise loves.

To deal with her humiliation and anger in a healthy way — and to try to educate men on its effects — she often makes harassment part of her standup comedy routines. With her propensity for outspokenness it’s frustrating that in the moments harassment happens — say that time she was asked for her underwear while walking downtown — she feels silenced.

“Yelling back doesn’t seem to help and it’s almost always when I’m alone, so in those situations I’m not in a position of power and I don’t feel safe,” she says.

“It’s also often shouted at me from cars, that seems to be a real trend.”

Equally frustrating for TerHart is that she doesn’t feel street harassment is a central concern for those with direct interest in the health of downtown. TerHart said she recently met with city councillor Scott McKeen to discuss street harassment but felt nothing happened as a result. (McKeen, on the other hand, says he plans to follow up with TerHart and discuss hosting an anti-harassment event. And he asks that women who face harassment downtown contact his office.)

Equally frustrating for TerHart is that she doesn’t feel street harassment is a central concern for those with direct interest in the health of downtown. TerHart said she recently met with city councillor Scott McKeen to discuss street harassment but felt nothing happened as a result. (McKeen, on the other hand, says he plans to follow up with TerHart and discuss hosting an anti-harassment event. And he asks that women who face harassment downtown contact his office.)

TerHart also says sexual harassment and assault were absent from the safety section of a recent survey conducted by the Downtown Business Association; homelessness, meanwhile, was mentioned three different ways.

TerHart says she uses her privilege and the channels available to her as a white, educated woman to advocate for herself and other women in the neighbourhood — she’s cognizant of the fact sexualized violence disproportionately affects homeless, marginalized and Indigenous women. Still, she says she’d like to see at least some of the responsibility placed on the perpetrators.

“Right now in Edmonton there are no consequences for street harassment. At what point do men start to realize that this is damaging and hurtful, and there are consequences for this behaviour?”

Learning what it feels like

That’s exactly what Zanette Frost, supervisor of programs and initiatives at the City of Edmonton, says the city is working to encourage through its Gender-Based Violence and Sexual Assault Prevention Initiative. Convened in 2015, the council initiative has been working with groups like Hollaback Alberta, SACE and Men Edmonton, a group that aims to promote healthy masculinity, to educate the public, particularly men, on what gender-based violence is. They also aim to encourage bystanders to safely step in when they see it happen.

So far, projects have taken place in pockets. For instance, the initiative conducts lunch-and-learns with corporate or religious organizations and has partnered up to present public screenings of the documentary The Mask You Live In, which explores how our narrow definition of masculinity affects men and boys. An interactive art exhibit, This Is What It Feels Like, had a mini-tour on the U of A and MacEwan campuses just before Christmas, giving men a chance to step inside a booth where they were subjected to harassing comments that women had reported receiving on the streets of Edmonton.

While art installations and documentaries might seem like a soft response to what is a serious social problem, Frost says getting men to realize how they are complicit in or contribute to sexualized violence is the first step toward shifting a culture that promotes it.

“My thinking has always been that if it prompts a couple of questions then there’s something changing. That’s what we hope for,” she says.

In 2018, the City of Edmonton will roll out a widespread awareness campaign dubbed “It’s Time” (to end gender-based violence) with a website, video and coasters distributed at bars and restaurants.

The campaign has also partnered with Edmonton’s CFL team, the Edmonton Sports Council, 630 CHED and other organizations with the aim of bringing the message to sports games, festivals and other public events. According to Frost, the City hasn’t yet reached out to the Oilers Entertainment Group to join the initiative due to limited staff, but it may do so in “phase two” of the project.

This spring, the City is also due to complete an exhaustive study of how and where gender-based violence takes place in Edmonton. This work began as part of the United Nations Safe Cities and Safe Public Spaces program, which Edmonton joined in 2016. Results of the study will inform policies and initiatives to combat violence against women going forward.

“We’re really working to end all that violence within a generation,” Frost says.

All of that’s hopeful, but it’s still a Band-Aid solution for the arena district, says Kyle Whitfield, an associate professor in planning at the University of Alberta who specializes in planning for vulnerable communities. She describes the area as one that seems to have been planned around hyper-masculine industries without regard for the experience of women. She also notes that planning is still a male dominated field, and, as a result, the design of public spaces seldom looks at the needs of women — even as accessibility for other groups, such as those with disabilities or seniors, are now routinely taken into account.

“It seems kind of old order to say we need to plan about issues related to women,” Whitfield says. “This is 2018, you’d think we’d be way beyond that, but we’re not.”

Oilers fans leave Rogers Place along 104 Street. Photo: Mack Male

The City has recently adopted a policy to apply gender-based analysis to all of its decision-making, from budgeting to planning, Frost says, but that wasn’t in place when the arena district was developed. It’s unclear whether the tool will be applied to the remaining phases of the development.

In cases where vulnerable populations haven’t been included in the planning process, inviting them to assess the space afterwards can be crucial in correcting elements that make them feel excluded or unsafe, Whitfield says.

“If we got a group of 50 women and we said, ‘Come and assess the Ice District in general and tell us how this suits your needs and how it doesn’t,’ I think there’s some value in doing that.”

Susan Darrington, executive vice president and general manager for Rogers Place, says her organization held two years of consultations with community stakeholders, including community leagues, the Downtown Business Association and social agencies such as Boyle Street Community Services, prior to the arena opening. While the issue of community safety was a frequent topic of discussion, she says women facing street harassment was never identified as a specific area of concern.

Going forward, however, Darrington says the Oilers Entertainment Group would consider partnering with the City on a gender-based assessment of Ice District or a public education campaign.

“We’d be open to having a meeting with them on anything they’re taking a look at,” she says, noting half the arena’s patrons are women and that her organization takes their concerns seriously.

“Our safety and security plan is for all patrons as well as people who are living and working in the downtown core.”

“We need to plan about issues related to women. This is 2018, you’d think we’d be way beyond that, but we’re not.”

— Kyle Whitfield

Angela Larson has a simple suggestion for making downtown feel safer: provide more reasons for different types of people to be out on the streets. Larson is the owner of Swish Vintage, located in Manulife Place, and says she’s perceived a marked decrease in street activity since she got her first job downtown at the age of 13.

Over the decade she’s been in business at her current location, she says she feels downtown’s mall-like areas have started emptying out as well, a reflection of changing shopping habits and a challenging retail environment. Swish is now one of the only street-facing retailers left on 102 Street and, increasingly, the only people Larson sees outside her door are either marginalized or “up to no good.”

Men frequently come into her shop and verbally assault her. Compared to when she was younger and catcalls were more suggestive in nature, Larson says at 52 the comments she gets now are more aggressive — “women-as-bitches kind of thing.” She even had one guy grab her phone and start to make a drug deal. As a result, Larson, like many other retailers in Manulife Place, doesn’t stay open in the evenings. During the day, a security guard is supposed to check on her once an hour, “to make sure I’m alive.”

While the arena promised to breathe new life into downtown, Larson says she’s seen little evidence of it.

Thousands of people now live in new condos in the area, but there’s nothing drawing them out onto the street. Rents along 104 Street are too expensive for small retail operators, she says, and retailers don’t stand to benefit from evening crowds heading to the arena.

“If I’m going to a concert, I’m not going to go shopping first and bringing my bags with me,” she says.

Getting the right mix of businesses and more life on the street is an ongoing challenge, says Downtown Business Association executive director Ian O’Donnell.

Bars and restaurants are often the only businesses that can afford the higher rents on 104 Street, although smaller retailers are starting to populate more peripheral areas such as Jasper Avenue or Rice Howard Way. While O’Donnell confirmed the DBA didn’t ask directly about street harassment in their 2017 survey, the issue did surface in the results — some people wrote it in under “other.”

“Certainly that topic was brought to our attention through that, but not at a significant level,” he says.

According to the results, general perceptions of safety downtown have increased since the last survey was conducted in 2010, with the arena drawing more interest to the area and boosting the police presence by 50 percent.

Still, O’Donnell acknowledges that if women are feeling unsafe in the area, at any time of day, that’s going to have a detrimental impact.

“The arena has certainly brought a lot of people a lot of money, and it’s helped the downtown from an awareness and an exposure standpoint,” he says.

“But if there are negative impacts and incidents, then that’s going to slow that. So we certainly want to make sure that we’re a part of that solution.”

Just what that solution is may be not be clear yet, but dedicated residents like Larson and TerHart are game to be a part of it.

“There’s a lot of big positives to living downtown,” says TerHart. “One community needs to make the effort to bring these changes.”

Written by Jessica Barrett. Photography by Ryan Girard.

Questions about this story? Comments? Get in touch with us.

*This story was updated March 6, 2018 to anonymize the name of a source. It was updated March 13 with links to other items in the series.

Disclosures

This story is part of a series co-produced by Edmonton Quotient and The Yards.

Published March 1: “A conversation about street harassment“, a video discussion about how Edmonton can start to make public spaces safer. Published March 13: “Women in the Core“, a live discussion recorded at The Yards spring salon.

If you enjoyed this story, and want to see more like it, consider supporting us.

Support EQ